|

Unpacking the messages of fat bodies as depicted by Slow Tarot

First, I want to start off with the following:

A few months ago I greedily unwrapped the Slow Tarot by Lacey Bryant and was astounded by the lusciousness of the art, the sweetness and depth of the deck, the kind rendering and interesting interpretations of each card.

But one card stopped me short. In fact, it made my blood ran cold and turned what was otherwise a joy into sorrow. The artist had decided to rename the Devil card as ‘Temptation’ and in it you see a tableau of (thin) people making love but mostly in the middle of the frame you see a naked fat woman squaring you directly, but her face is also square with the viewer but she is looking away. She is an object to be viewed by the audience’s gaze. It is a vulnerable, sullen shot. She holds an almost empty wine glass while around her lie plates of half eaten food and empty platters. The foods include cakes, cheese and grapes. Forbidden foods, indolent foods, foods of pleasure, “naughty” foods. The colors used to paint her are in a green cast. So what? You might say. What’s the big deal? But what if I told you that the deck contains no other image of a fat person? How would you feel knowing that the artist herself is not a fat woman (but I do not know what her journey has been. I only know she passes as a straight size now and that confers its own level of privilege). Here is the image:

As a fat woman staring at this image, what am I to think? What am I to feel?

Is it true that I have just handed myself over to Temptation, the Devil, and the underlying message: the sin of gluttony? Is my body really the bad guy, here? As a person who identifies as fat I have grown accustomed to living in a body that is often another woman’s greatest fear. The years of bullying and abuse from children and adults alike is nothing new. In fact, as a tarot reader I had long resigned myself to the fact that most tarot imagery will never look like me (though thankfully that has changed as artists are being mindful in creating tarot populations with diversity). But what is the emotion that someone who looks like me-whether that be me as a reader or a client who comes to see me, what do they feel when they see that image? I took it public and I asked others. I posted it on my facebook feed and it was clear: Shame. Women, but especially women who negotiate a fat body (or just struggle with weight) felt shame when viewing the image. That increased when they were told that there were no other images of fat women in the deck. And why would we feel shame? Because society has told us that we are moral failures. We fail as people, but especially, we fail as women when we cannot maintain a straight size and oh boy, shame sells, it really does

Again, so what? Maybe these people need to be shamed, am I right? Since obviously, they are fat because they have been led astray by the Devil. They are fat because they have no willpower. This is the long held view of fatness in the western world.

But these stereotypes have actual consequences for larger people in the real world. When fatness is viewed through the lens of personal and moral failing, it has huge social, financial and lifestyle impacts on people of size. “ Some 62% of people surveyed by the World Obesity Federation said they had been discriminated against because of their weight.” (BBC) The discrimination runs deep: fat people do not get access to medical care on par with straight sized patients. Many fat people are told that their problems are due to their weight and as a result their very serious medical conditions such as a crushed back or endometriosis or even breast cancer go undiagnosed and untreated. “The general public, in most Western cultures, is conditioned to condemn overweight individuals.” (Healthline) Fatness is condemned because it is a physical reminder that gluttony, temptation, sin, and depravity are the user’s fault. We live in a meritocracy- we believe that people deserve what they get in life. So fat people understandably deserve contempt, derision, bullying, fear, and even loathing. Don’t believe me? People surveyed would rather lose a limb or a year of their life than be fat. In our culture to be fat is feared more than almost anything else. Doesn’t that just sound crazy? I mean, think about it! People would rather lose an arm than carry weight on them. Now, what kind of cultural pressure is there that these people are responding to? It makes total sense that a meritocratic society condemns fat people so vociferously. You can’t help it if you are disabled, a woman, or mentally ill but (according to research that’s being rapidly debunked) you can help it if you are fat. And since fat is the one thing you can control then it is open season on the fatties! Our culture exonerates or villifies based on content of character

But if 60% of all Americans are now overweight and obese can we therefore posit that all of the sudden a huge swath of the population just suddenly lost their will power and are guzzling down bags of cheetos at 3am? Are we really ready to condemn the majority of the population when we look at this situation with a critical eye?

Because the research is beginning to show something very different. That, in fact, will power has not much to do about losing weight and keeping it off. The research has been very clear: in most cases dieting simply does not work long term for most people. How is it that the diet industry (which makes billions every year) can even stay in business if fat people are such gluttonous and lazy slobs if dieting actually worked? Or, if they just didn’t diet at all? With a 95% failure rate you can guess it is not the people who are already thin keeping these guys afloat. You guessed it, it is fat people who fail over and over again, who keep trying even when the research clearly shows that restrictive eating often harms their metabolisms and over time will make them regain the weight and add more on. There are hormonal reasons why people regain the weight they lost over time, this is a fairly new area of research, but it thoroughly uncouples the notion that being fat just means that we lack will power-that we have given ourselves over to temptation/devil. “Our study has provided clues as to why obese people who have lost weight often relapse. The relapse has a strong physiological basis and is not simply the result of the voluntary resumption of old habits,” he said. (Nutrition Review

“But, but, but… what about their health?!” is a common response to articles such as mine. But usually, health concern is just more thinly veiled fat disgust and stigma. Because if we really are concerned about someone’s health we would also be concerned about the greater constellation of their lives. The social, political, economic and access to care that affects the size of bodies.

We would be curious about the complex, interwoven pieces that health represents, and we would understand that weight is complicated and sometimes even beneficial to our health. It is called the Obesity Paradox and persists despite rabid attempts of debunking by medical establishments. It is no accident that weight is tied to economic class. The poor in America-that is another ‘free for all bias’ because in a meritocracy it is your fault if you are poor, too

So if dieting has such miserable success rates, why do fat people keep trying?

Because they know that to live in a fat body means the world can judge you at a glance and find you wanting. That glance means not getting a second interview, a date, the good loan. Being just 15 pounds overweight means a loss of $9,000 a year in wages. Fatness is not a protected class yet people are regularly discriminated against because of it. And, the saddest thing is that most fat people blame themselves, have internalized the world’s message and absolutely hate themselves despite trying over and over again to become thin, who want it more than anything. Of course many thin people scoff at the idea of fat stigma just like white people often will scoff when black people share their experiences or men discount the harassment that many women face all of the time. It is easy to discount a lived experience you have never had. If you have been thin your whole life you might have never seen any kind of fat bias, fat bigotry, and fat hate. This is called thin privilege and yes it is a thing. I would have hoped that the artist had taken just one small minute and imagined herself as a fat woman and asked herself, “How might this choice of fat devil make me feel as a fat body? Is it my role to paint this in this way? What is the message I am trying to convey? (and also) Might I be hurting people?” This kind of stuff honestly doesn’t take long. Just a minute of putting yourself in someone else’s (wide-sized) shoes.

I hope that I have made a clear case that imagery such as the Slow Tarot’s “Temptation” (i.e. Devil) card is not innocent. It reinforces harmful tropes about fat people and these tropes affect the very quality of life that fat people.

But mostly, it just hurt me.

It is more of the same. Here I am going about my business of living my life and all the sudden it is like getting slapped. Because, honestly? I am pretty happy in this fat body of mine. I like it. I like who I am. But it is society who constantly reminds me that I am not ok. That I am given over to the Devil, that I represent a cardinal sin and for that I get no quarter and certainly no pity. In a meritocratic world I get exactly what I deserve. As a fat women I feel that there is a constant quiet stream of hatred that only takes a little bit to come out. The woman who screamed, “You just a big fat woman, aren’t you?” when I yelled at her cause she almost hit me at a crosswalk. To the (ex) friend who posted publicly posted on Facebook, “So glad to cut the fat out of my life.” and left that status public so I would see it. To the man who gave me a look of disgust when I sat in his row on a flight. To the well-meaning condescending people who say they are “so proud of me” because I can swim laps in a pool, or out-walk them or out-dance them, shocked that I actually am capable of something that maybe even they are not. To the woman at the market stall who told me that “The bracelet looks so good on larger women like you.” and another who recently told me that “you look so well put together as a larger woman” as if to look good and also be fat was an equation she could not compute. These veiled compliments are mini quakes of hate. To the doctor recently who told me she was concerned about my BMI and told me to “just work out more” even though I came in because I thought I had broken my foot

As a professional tarot reader I am conscious about the decks I use when working with others. I am careful to choose decks that mirror the great and wonderful diversity of clients that I serve. I want my clients to see themselves in the cards because tarot is literally talking about the story of their lives.

As a reader, I want a deck that makes me feel grander, see bigger, reach further. Shame doesn’t do that. Shame makes one small. It would break my heart to use Slow Tarot and have this card come up for a fat person, to feel them still in silent hurt (most fat people have learned to just shut up and put up) to feel them close down. Or, to feel the heat in my face when this card came up between myself and a straight sized client-however am I supposed to be able to navigate that?

You know who I want depicted as a fat woman? Strength. Because to be a fat women in a thin world that barely hides its disgust means to don the heart of a lion, the strength of the desert, and the mental fortitude of taming the internalized shame and self-hate into something usable, even joyful.

To be a fat person is a crucible, a melting point where we negotiate our bodies and the spaces our bodies inhabit, it is a balancing act that actually requires great subtlety, sensitivity and a compassion for suffering-certainly not qualities that the Devil illustrates. The fat women I have known and hope to know are beautiful, strong, disciplined, capable, and credible. Let them be Strength, let them be Star, let them paint the firmament with the qualities I know them (and myself) to actually possess.

3 Comments

When I was very young I lived not more than 5 miles from the US-Mexico border (San Ysidro, what’s up?) While I am not of Mexican descent, I was heavily influenced by my Mexican teachers, classmates and friends in ways that reverberate even though I am now very far from the Baja California that feels like home. It is no wonder, then, that as a college student I was naturally attracted to cultural anthropology. From what I learned in my studies, it is second nature for me to see the underlying human condition that the archetypes of tarot typify. The Hanged Man, in particular, has so many cultural parallels that it astounds me. In fact, I am convinced that the Hanged Man is one of the most important (yet, sadly, underrated) cards in the deck. This card is incredibly powerful, unbelievable ancient, and supremely intimate. As an adult looking back into my early memory, there are fragments of childhood fascination that entered my cosmological make up. One of these was a fascination with in the once indigenous (now Mexican) Danza de los Voladores. Pictures and graphics of these men taking flight were on my textbooks, and also I have one faint memory of seeing them in action.  By B.navez — Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5161492 By B.navez — Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5161492

As stories go, this ancient ritual was created when the people wanted to appease the rain god, Xipe Totec, so that the rains would appear and the land would grow again, but there any many variations to this story.

This is one example of how, throughout history, throughout vastly different cultures, voluntarily hanging oneself is a means of opening the communication channel to God. I refer to the Hanged Man as the ‘check engine light’. We get the Gods’ attention by turning ourselves upside down, “Pay attention to our plight,” we cry. “Help us with our needs. See how we brave this for you? See how we hang for you? See how we humble ourselves for you?” We also, in some sense, emulate for a moment what we think a God might be like, soaring through the sky unencumbered, we gain a new perspective on the world.

The now ubiquitous bungee jumping also has ancient roots. Before it was appropriated, it was known as land diving on the southern Pentecost Island of Vanuatu. The people would erect wooden towers of up to 90 feet with their feet tied with jungle vines.

The lower platforms are for young boys who dive as a rite of passage into manhood while the highest platforms are for feats of courage and strength.

The Hanged Man is a rite of passage to ever greater spiritual maturity. We hang to ripen, we hang to show God and society that we are capable of handling things that scare us. We test the known boundaries of the world both desiring to be like God and also currying God’s favor. We show the Gods that we can endure. We prove to ourselves we are capable of delayed gratification. We teach ourselves that we must give something to get something. The Hanged Man is an exchange. The Hanged Man is bartering.

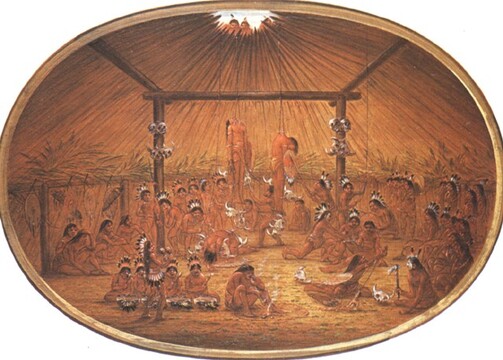

The Okipa ceremony originates from the native North American indigenous people, the Mandan. The ceremony was tied to their complex creationist stories but also became a complex series of endurance tests for young men looking to please the spirits.

“The Okipa began with the young men not eating, drinking, or sleeping for four days. Then they were led to a hut, where they had to sit with smiling faces while the skin of their chest and shoulders was slit and wooden skewers were thrust behind the muscles. With the skewers tied to ropes and supporting the weight of their bodies, the warriors would be suspended from the roof of the lodge and would hang there until they fainted. To add agony, heavy weights or buffalo skulls were added to the initiates’ legs.” (Wikipedia)

Those finishing the ceremony were seen as being honored by the spirits; those completing the ceremony twice would gain everlasting fame among the tribe. This ceremony has echos in a modern day Hindu ceremony called Charak Puja. Honoring the the God Shiva by acts of personal sacrifice means he will bless the land and people in the upcoming year. In this festival young men will also swing from poles using metal hooks that have been placed through the skin of their backs.

Our new perspective, through pain or through flight, through being upside down, or flying across the landscape, gives us the same kind of non-ordinary reality that shamans use to connect to a unified field of divine experience.

While this may seem inconvenient, if not downright gruesome, to modern eyes, it remains that the Hanged Man is an ancient archetype. I don’t want to put metal hooks in my back, but I can appreciate what sacrifice, bravery, modesty and inquiry means as a technique for getting to a new level in my spiritual relationship with the divine.

The Hanged Man is a detested card when it shows up in client readings because its appearance means that the person asking the question is not going to get what they want in the way that they want it. They are often being asked to adopt a holding pattern of asking without demanding the answer.

Fear of what the Hanged Man teaches is a core principal of modern society. A society that blocks individuals from greater connection to the Divine. This flies in the face of what we are normally taught in modern, secular culture. When we let go of ego, we are telling God we are ready to talk. The Hanged Man is the Liminal Aspect of Passage. As a professional reader, I can tell you for a fact that it is exactly when people are approaching (or in) their own versions of a Hanged Man that they come for a reading. Whether it is divorce, illness, job loss, or bankruptcy these clients are in liminal space. “What will happen? How will I get through this? What will this look like on the other side? Why me?” They ask. We all want to know the final outcome. But holding space for not knowing, for being the ‘check engine light to God’ that I talked about is a powerful (and necessary) part of the process to change. Damn right it is uncomfortable. It is absolutely hard and a lot scary. This is part of the journey, is required by the journey. Rites of Passage have three inherent elements: separation, liminality, and incorporation. First, we take ourselves away from normative experience by undertaking an unusual physical task. Then, the task we have chosen pushes us into liminal space, that is space that is inherently discombobulating and unclear. This is the space where we are choosing to no longer be in control. Disorientation in this step is not only encouraged, it is absolutely a required element in a personal rite of passage. The Hanged Man is the liminal aspect of the rite of passage. Without embodying the Hanged Man, we are denied passage to the other side. Finally, we have incorporation. It is only through the passage that Hanged Man delivers that we can meet Death, the next archetype in the major arcana. In this sense, Death is the death of an old identity (boy to man) or (plebeian to shaman). Once the old self dies in some aspect, can we be reincorporated into normative society as the new, shiny being we have become. Have no fear, reentry is part of this process

How to Create Your Own Modern Day Hanged Man Experience

For the purposes of the Hanged Man, I think we have to consider that there must be a physical element to the process. Our body must also be involved in the rite we wish to enact. But our society inherently eschews anything dangerous, so it hard to create the conditions that ancient humans utilized to push their spiritual consciousness to the next level, but here are some ideas: Roller coasters Bungee jumping Sky diving Deprivation Tanks Hang Gliding Deep Diving Rock Climbing Free Climbing Cliff Diving Aerial Yoga Ariel silk dancing Ritual dancing Ayahuasca (Shamans use psychoactive drugs to create a rite of passage, I guess this would be considered a hack.) Even moving to a new country These are just a few ideas, please share yours below! I hope I have convinced you to see the Hanged Man as an incredible aspect of the human condition. When the Hanged Man appears in a spread, I take notice, smile a little, and take my hands off the wheel.

The last couple of months have been challenging because I live with chronic migraine. My health dictates what I can and cannot do.

I have to limit how much I work, my exposure to noise, light, stress, and wine (oh, sweet heavens not the wine, too!). But in the ways that it has limited me, it has taught me so very much. What I have learned from my illness is that people are uncomfortable around hurting. It is so anxiety producing that the first thing a person grasps is to try to fix the dysfunction. We are not taught how to bear witness to suffering. We have not learned that our kind and loving presence is enough (it is). If we cannot fix it then we don't know what to do with ourselves. It feels like actual help when we toss off a recommendation, “Have you had enough water?” or “Did you try X, Y, or Z?” What do I know, what have I experienced that might help? Surely more information is needed! Perhaps I hold the key to help this person! Our suggestions alleviate the anxiety we feel. The certainty of giving a suggestion feels so much better, doesn’t it? Wrapping up a problem with a bow feels so good! “Just try this one weird trick!” But what I have learned is this: those who suffer are the experts in their own pain. Wide awake at 3 am on the 10th page of Google we pull together all the fragments and try to stitch together what makes sense. It is amazing how knowledgeable we become on the nature of our suffering whether that be physical, emotional, or spiritual. You are an expert in your own pain. And as an expert in your pain you probably know far more than those attempting to help. As an expert in your pain you require something other than a suggestion or recommendation. As the expert, you know exactly what you need. What broken heads or hearts need is emotion, action, and presence. Perhaps a trip to the grocery store, or run a load of laundry, or swoop in with a diet-busting gallon sized container of chocolate-chocolate fudge. But first, the most important thing to say to your beloved one hurting is this: How can I help? This question changes the dynamic. We lay ourselves down as servants to the afflicted, we hold space for them. Leaving room for uncertainty, for endurance, for patience and for faith that cannot yet see relief is massively hard. And even if we do have a reason or cure, it does not always heal the wound, the heart, the spirit. I do not believe in noble suffering. I am no martyr. Pain is ugly. Pain is hard. Pain challenges who we are. Pain can strip us of our humanity bit by bit. But, pain can be eased somewhat by asking four words: how can I help? As a reader, I am no expert to your pain, you are. What I wish to be is a servant to what hurts, what feels broken, to hold that space to strengthen your resolve, your focus and to support your coping. As Ram Dass famously said, “We’re all just walking each other home.” |

Details

Subscribe below to get my daily blog posts right in your email!

Jenna Matlin

M.S. in Organizational Psychology and Leadership Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed